As Washington accelerates efforts to secure key supply chains, rare earths and critical minerals like gallium have emerged as strategic priorities for US industry and national security.

China has long used its dominance over strategic metals to apply pressure to the US, ramping up efforts in recent years.

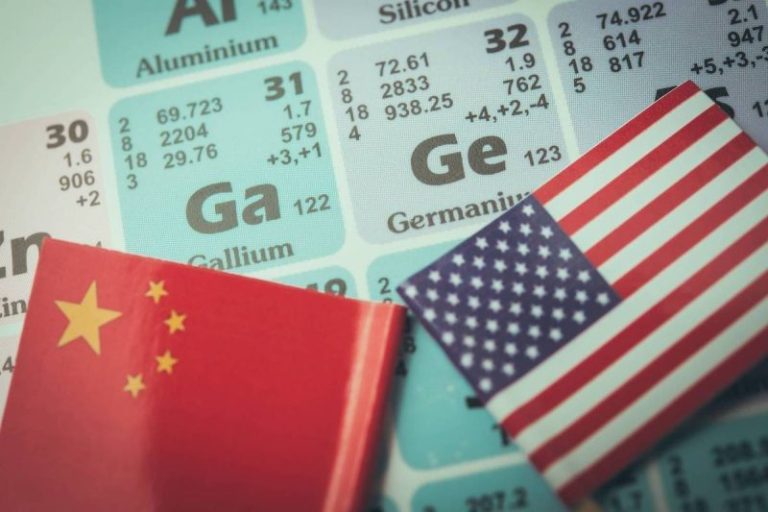

Beijing first tightened export licenses on gallium and related materials in 2023, and then in December 2024 effectively banned exports of gallium, germanium and antimony — all critical to semiconductors, defense systems and advanced electronics — to the US by refusing licences in most cases under its dual-use export control regime.

The move was widely seen as retaliation for US export controls on Chinese high-tech goods, and underscored China’s leverage in critical minerals supply chains. The restrictions created shortages for American buyers and forced some to source materials indirectly through third countries to keep production lines moving.

In late 2025, however, China suspended its direct export ban on gallium and related metals to the US, part of a tentative trade truce following high-level talks between US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping.

The suspension, which runs through late 2026, restores the possibility of exports, but keeps the metals on China’s broader export control list, meaning shipments still require government licences.

Harvey Kaye, executive chairman of privately owned US Critical Materials, says the US’ vulnerability has become impossible to ignore after decades of Chinese dominance in rare earths mining and processing.

“They flooded the market, made it uneconomic for others and then locked up assets worldwide.”

Today, China controls roughly 98 percent of rare earths processing, a concentration the US government increasingly views as untenable. Its concerns intensified last year, when China restricted exports of gallium, a metal essential to advanced semiconductors, radar systems and military hardware.

“There are roughly 3,800 military uses for gallium alone,” Kaye said. “When China cut it off, the geopolitical reality became very real, very fast.” US Critical Materials believes it has a potential answer.

The company controls 339 claims at its Sheep Creek project in Montana, where recent sampling returned average total rare earths grades of around 9 percent — significantly higher than most North American peers. More critically, the deposit is rich in heavy rare earths and gallium, which are essential for magnets, chips and defense applications.

“What makes this deposit unique is not just the grade, but the heavies — dysprosium, terbium and gallium,” Kaye explained. “That puts us in a very different strategic position.”

The company is positioning itself as both a resource and technology play.

In partnership with Idaho National Laboratory, US Critical Materials has developed what it calls a closed-loop, environmentally benign processing method dubbed “rock-to-dock” technology.

“Our goal is to go from raw material to finished product without destroying the environment,” Kaye said. “No effluent, no waste — and critically, processing done in the US.”

He added that the company expects visibility to early production and revenue as soon as 2026, helped by underground mining methods that avoid large open pits and minimize surface disturbance.

Federal interest is already building. Kaye confirmed discussions with multiple US agencies, including the Department of Defense, and said the company is open to government investment and offtake agreements.

“Found in America, processed with American technology and available now — that changes everything,” he said.

Looking ahead, Kaye expects greater collaboration across the US rare earths sector as policymakers push for supply chain resilience. “At this stage, we’re all Americans,” he said. “Competition matters, but cooperation matters more.”

Geopolitics, trade friction and the push to rewire rare earths supply chains

Rising geopolitical tensions between China, the US and Europe are accelerating changes in global rare earths trade flows, with long-term implications for supply security as 2026 approaches.

“Whether rare earths are truly ‘critical’ for individual nations is almost beside the point,” the expert said. “We seem to have decided, politically, to weaken trade between major powers. If we’re going to do that with China, we need to be prepared for continued supply instability in rare earths.”

That instability leaves western economies with two broad options: rebuild China’s vertically integrated rare earths supply chain at home — at a higher cost — or reduce dependence on rare earths altogether via new technologies.

“Either we recreate the Chinese supply chain in miniature and accept higher prices, or we innovate our way out of the problem,” Hykawy said. “That question is still very much open.”

Technological change is already offering potential pathways. Hykawy pointed to advances in electric motor design, including axial flux motors developed by YASA, a subsidiary of Mercedes-Benz Group (ETR:MBG,OTCPL:MBGAF).

Unlike conventional cylindrical electric vehicle motors that rely heavily on rare earth permanent magnets, axial flux designs use magnets more efficiently and may, in some applications, replace them with electromagnets.

“These motors require better materials and more precise machining, but they use magnets far more efficiently,” he said. “In some cases, they may even eliminate the need for rare earth magnets altogether.”

The example highlights how innovation could soften demand growth for certain rare earths over time, though cost and scalability remain barriers. At the same time, Hykawy argued that western efforts to localize rare earths mining, processing and magnet manufacturing are realistic, but will take patience.

“We are only at the beginning of building a rare earth supply chain entirely outside of China,” he said. “There is absolutely nothing that prevents us from doing it except time and money.”

Contrary to popular belief, Hykawy said rare earths mining is not more environmentally damaging than other forms of mining, noting that deposits — including ionic clays rich in heavy rare earths — exist well beyond China’s borders.

“The real constraint is people,” he said. “We need experienced operators, engineers and processors, and there is no shortcut for the time it takes to build that expertise.”

As trade frictions persist, Hykawy expects supply diversification to continue, but warned that near-term volatility is likely to remain a defining feature of the rare earths market through 2026.

Securities Disclosure: I, Georgia Williams, hold no direct investment interest in any company mentioned in this article.